Cybercrime and Developing Nations

The effects of grassroots vs state sponsored Cyber Crime

In April 2024, an international research collaboration unveiled the world’s first “Cybercrime Index,” an unprecedented attempt to map the global geography of cybercriminal activity. Based on expert surveys across five major categories of cybercrime — from malware creation to money laundering — the index ranks countries by their degree of cyber-crime threat. Below is the results of the that 2024 Cybercrime index from The University of Oxford

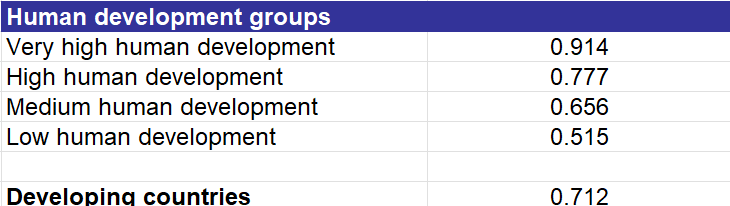

Several nations on the Cybercrime Index demonstrate technological advancement beyond the quality of life afforded to their average citizen. This means that people may have access to the internet and all the information on it. However, barriers still exist that prevent translating technological development into improvements in the average citizen’s lifestyle. The United Nations Development Program uses a system for assessing what most people refer to as quality of life called the Human Development Index (HDI). Below is a breakdown of how countries are assessed:

The HDI reveals that between half to two-thirds of the top 20 cybercrime nations exist in the Medium or High development brackets which classify them as developing or semi-developed nations. The majority of nations that serve as cybercrime bases or development centers for cybercriminal activity are developing nations that face educational and healthcare and economic development challenges. The development stage of many nations creates internal structural weaknesses that lead to cybercrime emergence as an internal threat rather than an external one.

The disparity between cybercrime and HDI becomes more interesting when you look at who is doing the hacking. For example, Nigeria ranks 5th with a World Crime Index score of 21, 4 points below the United States. No threat actor group from Nigeria has been labeled a nation-state, and the threat actors are individuals ranging from teenagers to people in their 40s. In 2021, Ramon Olorunwa Abbas, aka HushPuppi, pleaded guilty and admitted to laundering over 300 million. HushPuppi is a just one of many Yahoo Boys, the name given to scammers and cybercriminals from West Africa. Maybe you think I am being critical of Nigeria, but that isn’t the case. Cybercrime in Nigeria has actually led the way for major developments and legitimate opportunities within West Africa. None of this legitimizes the scams and cyber crime but many cybersecurity professionals have come from the area to make up for it. A great example of how West Africans have taken advantage of the opportunities of the internet would be the work done by Confidence Staveley and the CyberSafe Foundation project out of Lagos Nigeria, which took a positive approach to the utilizing the latent talent of the people.

This paradox — where regions burdened by economic or infrastructural instability also become centers of digital innovation — reveals an important truth: cybercrime ecosystems often grow out of necessity, not malice. In countries where unemployment is high and access to global markets is limited, the internet offers both opportunity and temptation. Skilled individuals who might have become software engineers, entrepreneurs, or cybersecurity analysts instead turn their technical ability toward cybercrime because it provides a faster, more reliable income. Over time, these informal networks of digital hustlers evolve into complex underground economies that mirror legitimate tech sectors — complete with mentorship, specialization, and transnational collaboration. Ironically, the same connectivity that fuels crime also becomes the foundation for technological empowerment and legitimate career paths in cybersecurity, digital forensics, and ethical hacking.

On the other end of the spectrum is the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) which does engage in state sponsored cyber crime. You will be able to find DPRK on the HDI chart but no score will be attached, possibly due to the lack of information needed to score the countries efforts effectively. Many speculate that this is done on purpose by the East Asian country to avoid the globally public black eye that the real data would give. Most cybercrime tracked out of North Korea is not a grass root civilian movement they are what the industry refers to as an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT).On October 22,2025 the United Nations released an 138 page report detailing how DPRK avoids sanctions through cyber campaigns. From January 2024 to September 2025 North Korea stole over $2Billion in crypto assets. One would think that during this time the average lifestyle of a North Korean citizen would be filled with the confusing complaints of those who live in luxury. The complaints aren’t similar to those of Ayesha Curry, looking to fulfill a need to be seen because all other needs are met. The voices cry out about hunger, power outages, corruption, crackdowns, and government control over every part of life, according to Radio Free Asia.

A comparison of cybercrime in Nigeria and North Korea directly demonstrates why crime in the hands of the people is a cry for help, resources, and could be the source of our mankind’s next great story of triumph. However when that crime is sponsored by the state the people suffer and only the ruling class sees the benefit. If we use the United States as a measuring stick then ideally cybercrime would be open to both the state and the people. The people bring attention to areas in need of improvement and use the advancements in technology to support protest, while the state protects the people from cyber war campaigns such as Salt or Volt Typhoon.

Cybercrime doesn’t emerge in a vacuum—it grows in the cracks of uneven development, weak institutions, and limited pathways to legitimate digital work. Nigeria and North Korea illustrate the two poles: one where economic necessity fuels informal cyber economies that can be redirected toward positive innovation, and another where state-backed operations convert hacking into policy, profit, and power at the expense of citizens. The lesson isn’t to excuse crime; it’s to understand the soil it grows in—and to change that soil.

Real progress means pairing enforcement with opportunity: invest in digital education, create entry-level cyber jobs, strengthen rule of law, and celebrate grassroots leaders who turn raw talent into public good. At the same time, nations must get serious about sanction evasion, crypto theft, and APT tradecraft that destabilize global trust.

For everyday people and small businesses, the path forward is practical: raise cyber awareness, harden the basics, and engage with communities that turn curiosity into capability. That’s our mission at Netizen Watch—helping Responsible Protectors build skills, spot scams, and defend what matters. If you’re ready to move from worry to action, start with our free crash course and join the Academy. The same networks that spread harm can also spread resilience. Let’s choose the latter—and write the next chapter on our terms.